Presentation at Cumulus Nantes 2025: "Ethical Leadership, a new frontier for Design"

Presentation of the short paper "Information as an Experience: A Visual Design Approach to Ethics for Building Relationships between Researchers and Participants"

Abstract

Design and social innovation research can be defined as a relational practice that is concerned with the emergence, through applied design strategies, of new social and material relationships within a group. Establishing a relationship between the design researcher and the community based on reciprocity and mutuality is then fundamental for successful research. This paper interrogates how this relationship is built during the recruitment phase by analysing how reciprocity and mutuality can be reached through an information design approach to ethical procedures. It focuses on the principle of informed consent and its role in defining the relationship between the researcher and the (potential) participants within the context of my PhD, which is a graphic ethnography exploration on how cultures of sustainability emerge in craft communities in Southwest England. Drawing upon the original meaning of the Latin verb informare, “to give a shape”, and defining ‘consent’ as a continuous conversation, I used my expertise as a visual design practitioner to create an integrated information experience that ‘gives a shape to the research’ to allow potential participants to have a comprehensive understanding of the project while creating the conditions for a dynamic conversation to take place. Initial exploration showed local maker communities as heterogeneous and dynamic groups with shifting hierarchies and demographics where roles, meanings, and values are renegotiated over time, hence the necessity for an integrated information approach flexible enough to both address ethical challenges and function as a tool for constructive relationships. The paper discusses the way this approach incorporates three fundamental elements of the research project, the methodology (graphic ethnography), the research object (craft), and the research ethos (sustainability and accessibility) by designing ad-hoc print and web versions of participant information sheets for different audiences, accompanied by an online showcase that gives a recognisable shape to the overall project. It concludes with preliminary observations collected through the first year of field work, and it engages with the limits and issues of creating ad-hoc information experiences to obtain consent. As the research is ongoing, this paper does not yet give a full assessment but is meant to start a conversation on creative approaches to ethical procedures. The aim is for these to become a tool to generate solid and informed relationships between researchers and participants.

Presentation Transcript (with slides)

This brief essay is the transcript of my talk at the Cumulus Conference Nantes 2025, presented on June 5th, available here as we wait for the proceedings of the conference to be published with the original short paper.

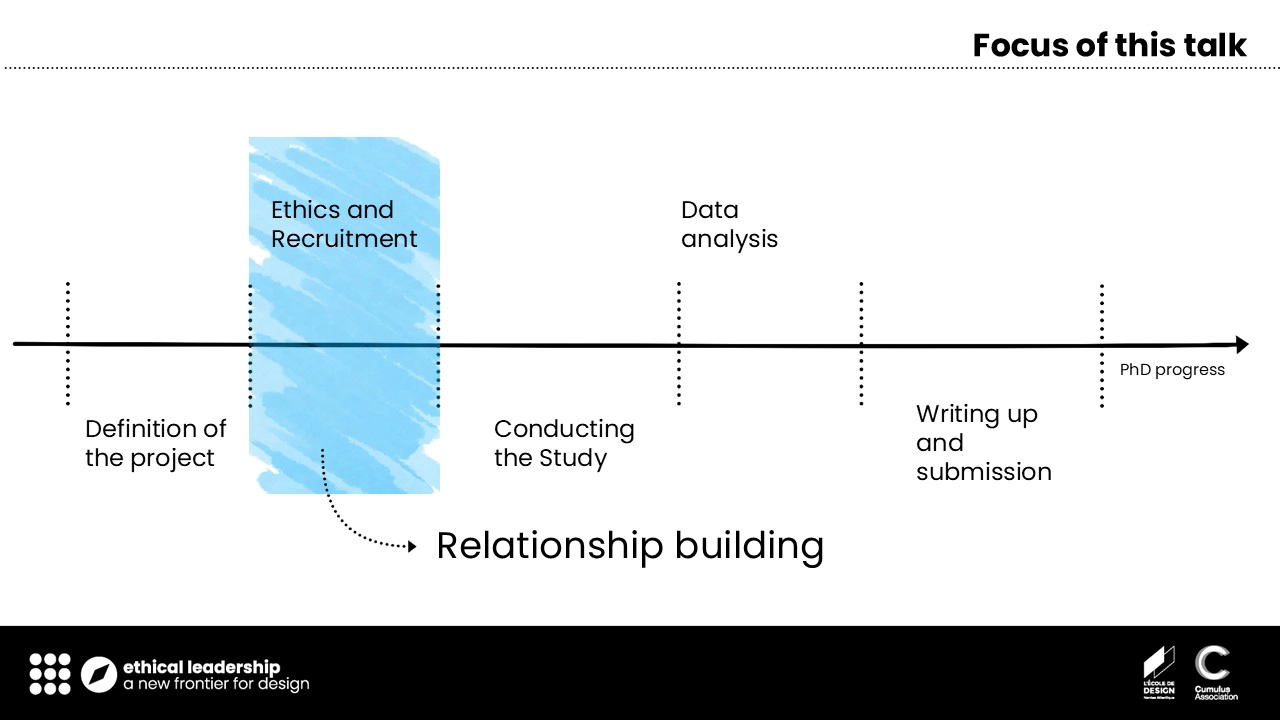

This talk focuses on a particular aspect of my PhD developed in the Ethics and Recruitment phase of the project, which is that phase between the definition of the research study and the data collection. Because I wanted to work with communities I did not know prior to my PhD, the Ethics and Recruitment phase was also the moment in which I needed to build and strengthen relationships with my (potential) participants, and therefore required a careful approach.

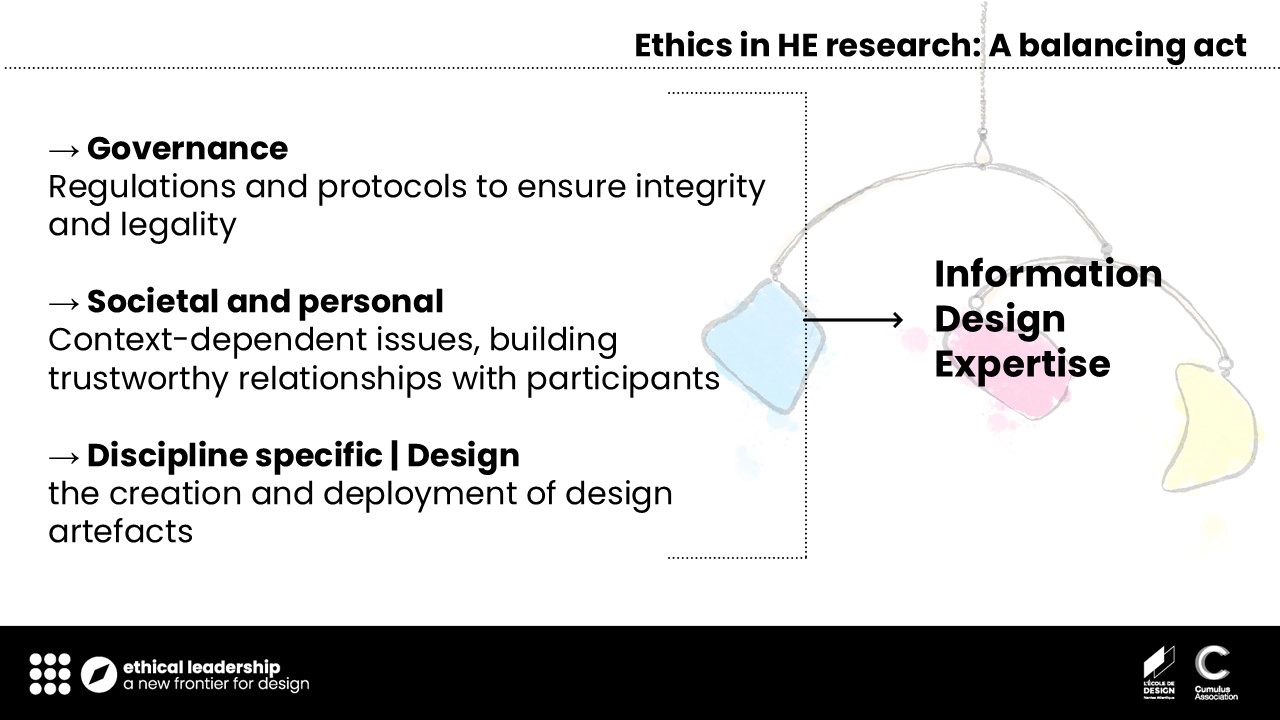

My experience of navigating ethics in Higher Education has been a balancing act between three different layers of complexity:

- a first layer, which I call Governance, are the university regulations, institutional protocols, and the legal framework we operate in;

- a second layer is defined by social and personal issues, i.e. our and other people's morals and cultural codes that need to be negotiated and that inform directly the kind of relationships we will establish with our research participants;

- and finally, a third layer, which is characterised by discipline-specific ethical issues. For example in my discipline of research, Design, one aspect of ethics needs to take into account the creation and deployment of design artefacts and their effects on society and the environment.

In this presentation, I show how applying my own expertise as a visual and information designer, which is what I do outside academia, helped me navigate these three layers in the context of my PhD.

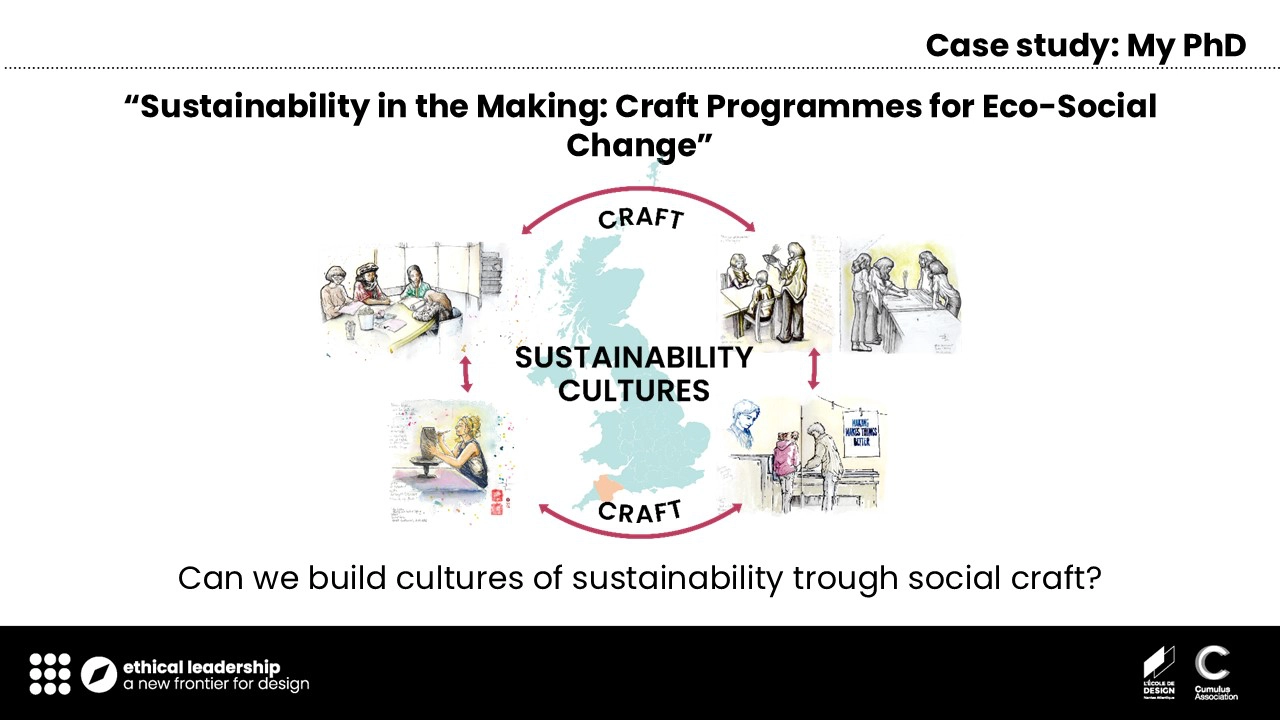

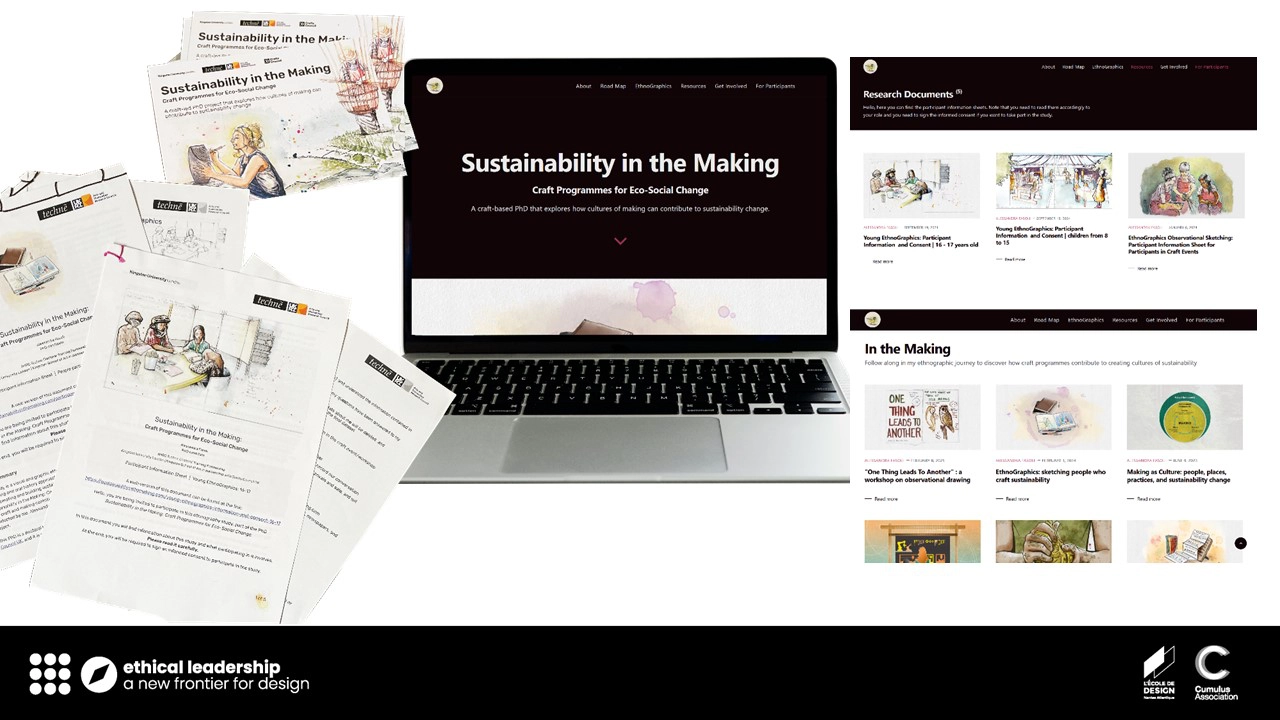

My PhD is currently titled *Sustainability in the Making: Craft Programmes for Eco-Social Change* and its concerned with the question on how we can build cultures of sustainability through social craft in Southwest England, specifically, in South Devon.

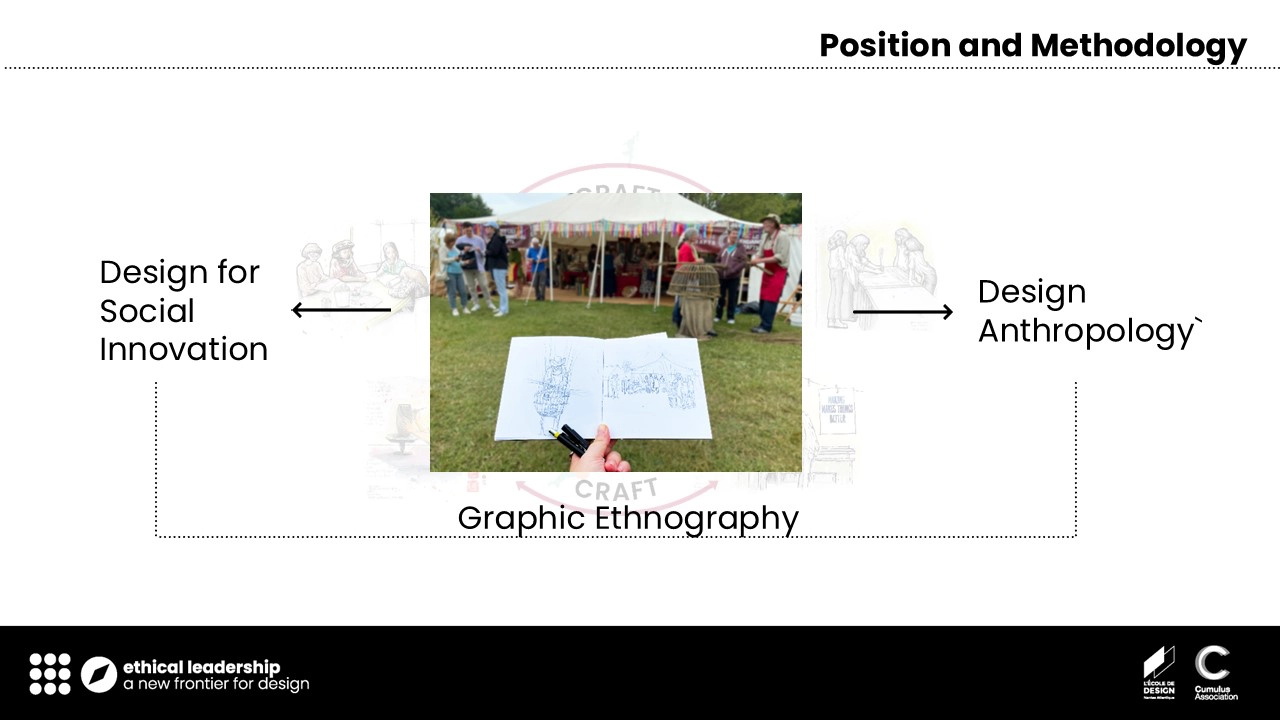

Within the design field, I like to position my project between design for social innovation and design anthropology; and I investigate my research question through a graphic ethnography approach, an academic complicated way to say that I join craft communities when they gather during workshops or fairs and I sketch them out and talk to them while they make.

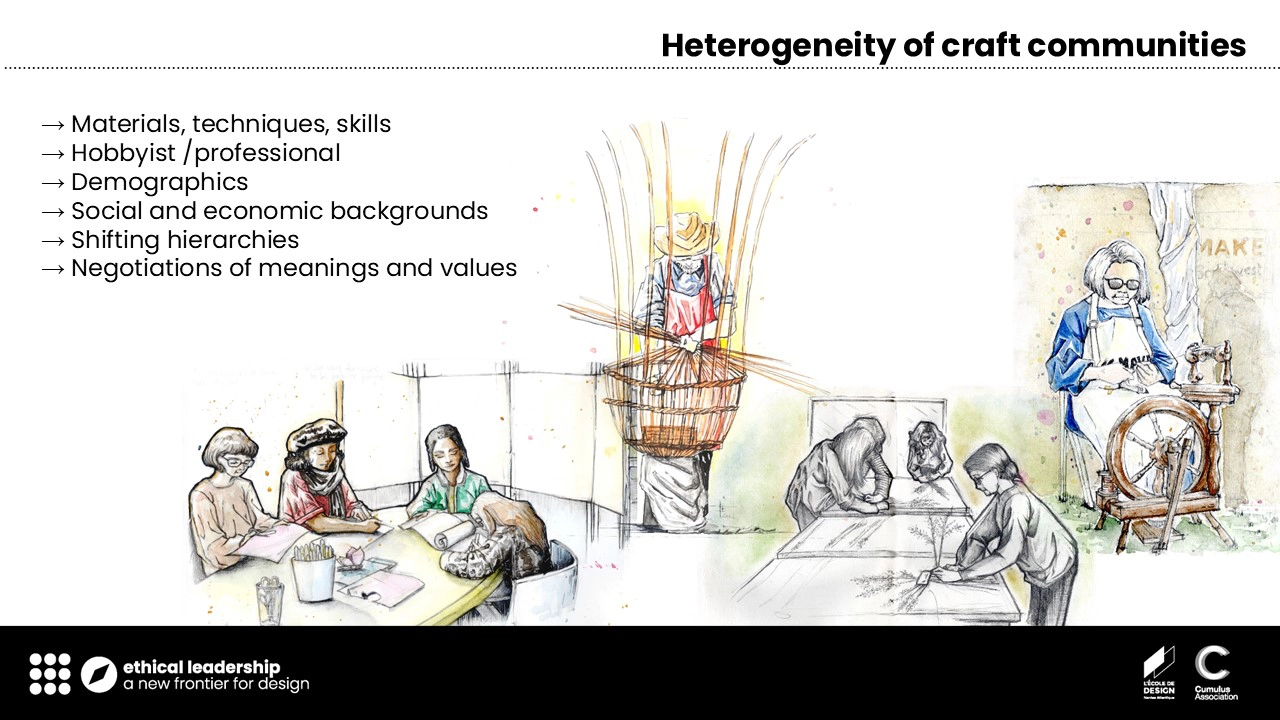

Working with "craft communities" presents a series of challenges, as these are heterogeneous groups which not only differs in the use of materials, techniques, and skills, but are also characterised by different levels of professionalism, demographics, and/or socio-economic backgrounds. Because craft workshops, gatherings, and fairs are ephemeral iterative events attracting each time different people, group hierarchies tend to be dynamic, for example, someone being a facilitator in a craft workshop once can be a attendee in another occasion, or in more informal groups there might be no hierarchies at all. This constant shifting of social organisation means that values and meanings associated to craft are constantly questioned and renegotiated in every new iteration of a social craft event or activity.

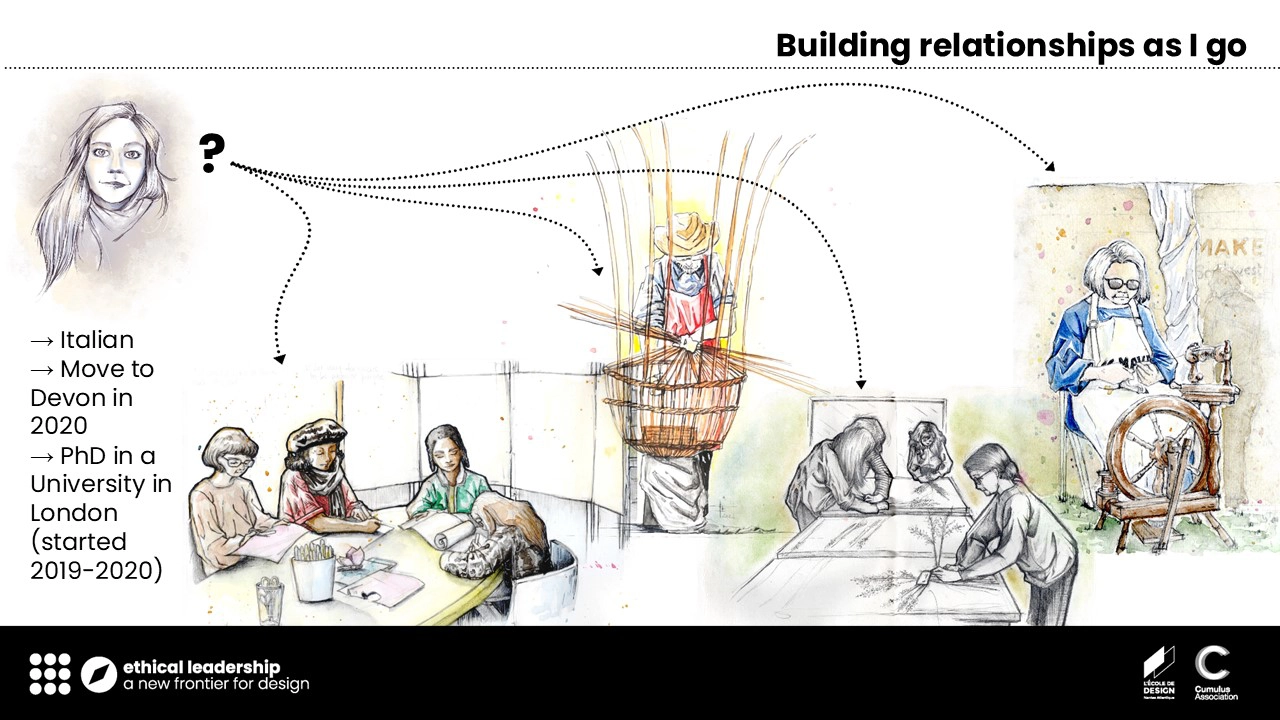

And then there is my peculiar position towards those communities, firstly as an Italian coming from a different craft tradition. I started my PhD at Kingston University London in 2019 (while still based in Rome, Italy) and only moved to Devon in 2020, with no prior knowledge of the craft ecologies of the region. Because I am trying to understand Southwest craft in its own terms, I needed to build a whole new set of relationships from scratch as the research progressed; a process that also required a renegotiation of my own personal concept of craft. On top of this, I also have to navigate two different positions, one as as a designer and illustrator and thus new member to the local creative, and the other as an external researcher who is associated to a university in London.

The recruitment phase became then the occasion to build and consolidate these new relationships. In standard ethical procedures, recruitment is based on the principle of *informed consent*, which, as per the Social Research Association, means that:

"information can be collected from or about people only if they have understood the purpose of the research and what their participation entails, and have freely agreed to participate in it."

In the literature, consent is often described as a "negotiation" and a "conversation", which implies that consent is not a static, one off yes or no answer, but it varies as the project progresses and participants gain more insights that will inform their role in the research. This means that the informed part of the informed consent is the result of a process: information is an experience.

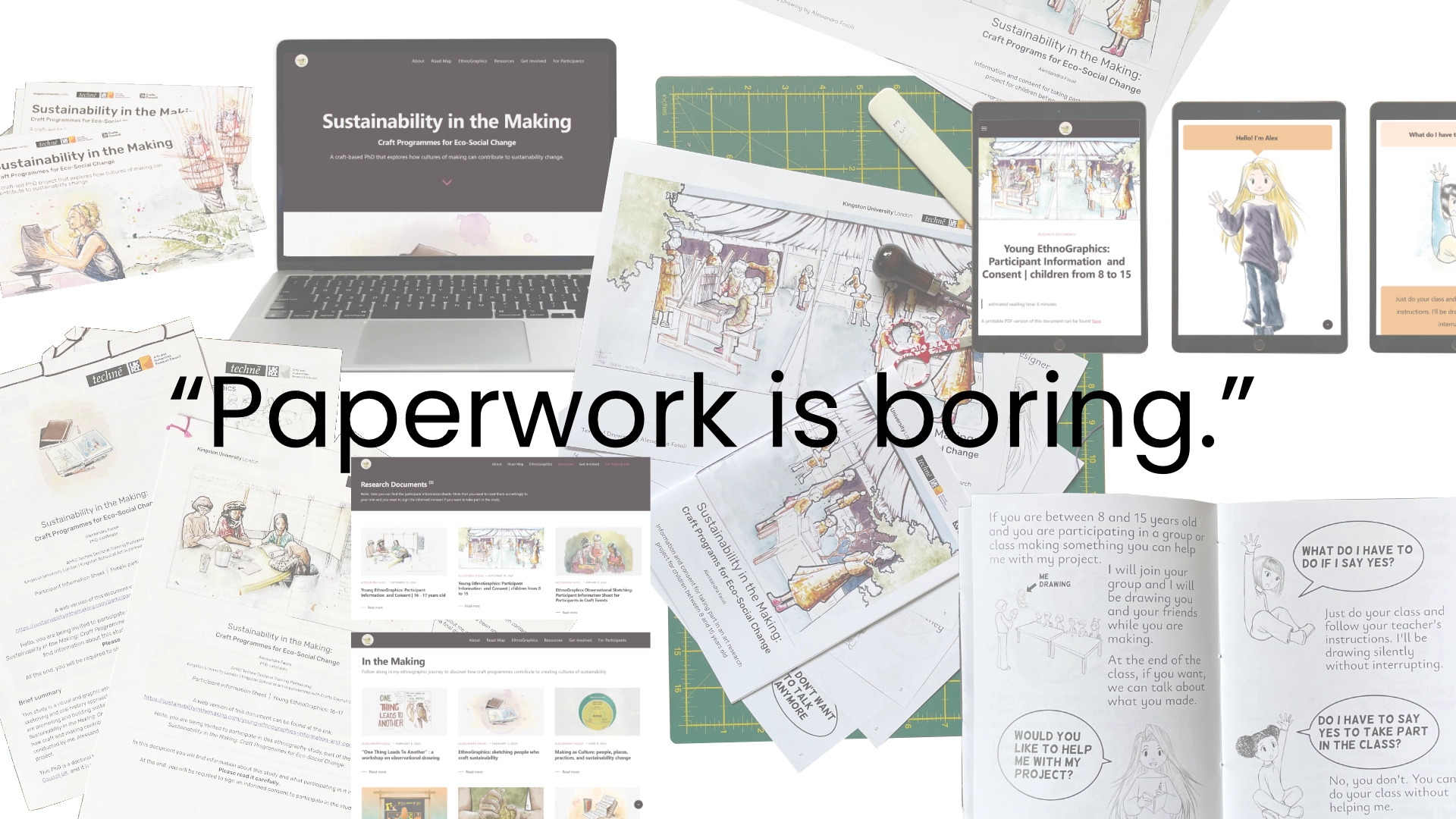

Or so the theory goes, because when I looked at the tools that are generally employed to seek participants' consent, this progressive aspect on how information is acquired and then applied in decision-making processes is lost. In standard ethical procedures, the tool to seek *informed consent* is the "participant information sheet", a document that contains a comprehensive description of the research, all details of what is involved in participating in the study, the risks associated with it, and participants' privacy and data legal rights. Universities generally have text-file templates that their researchers can use, which end up being very dense documents that fix information in a static long-form text and require close lengthy reading. Information, instead of an experience, becomes paperwork.

The participant information sheet is a mandatory document in the university's ethical procedures, but the institutional templates are not suitable if you are trying to build mutual and reciprocal relationships while recruiting your participants, as in my case. So, I did what I always do when I need to find some clarity: I consulted the etymological dictionary, which provided me with a crucial insight: information comes from the Latin word informare (to inform), which means 'to give a shape, to give a form'. If the act of 'getting informed' is an experience, then to inform is giving a shape to that experience. And there is a profession that shapes experiences: design. And I just so happen to be a designer.

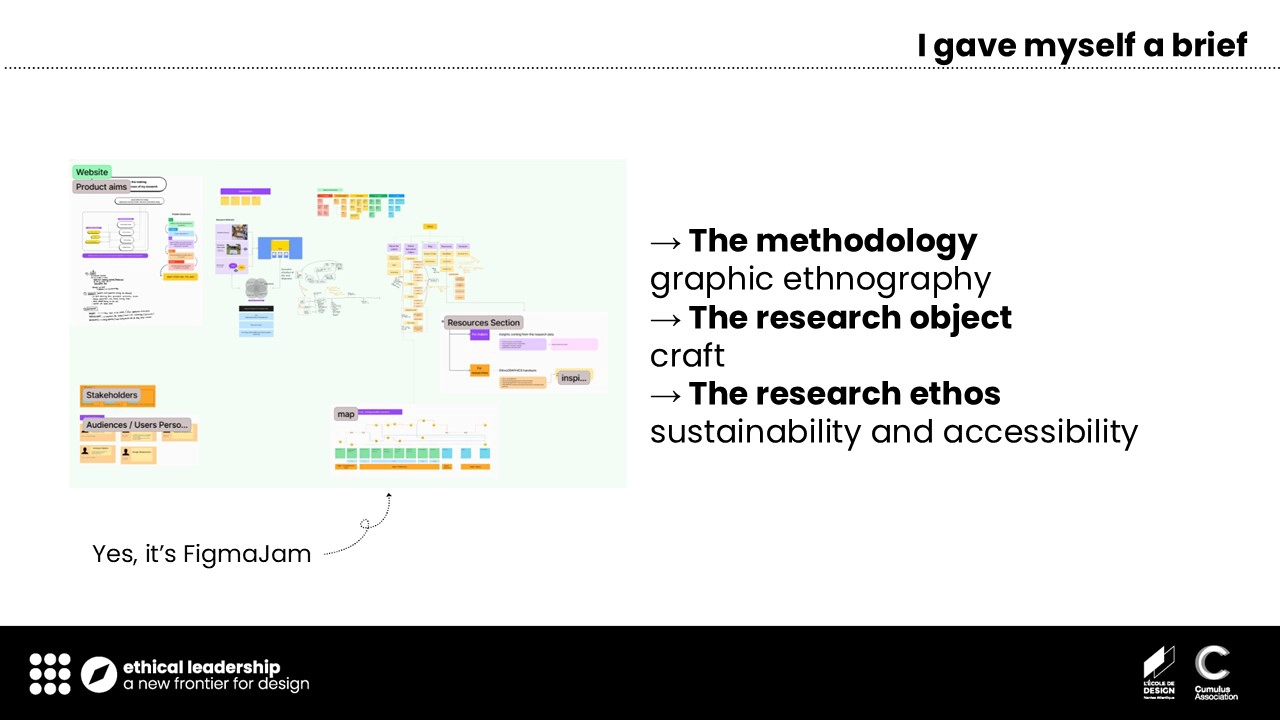

What if, I asked myself, I approach the Participant Information Sheet — and ethical research documents in general — as a design problem? I decided to give myself a brief, in which I defined that the documents final form should reflect and be coherent with the three core aspects of my research:

- the methodology: graphic ethography;

- the research object: craft;

- the research ethos: sustainability and accessibility.

I decided to treat these core aspects not just as guiding values, but as affordances, and brainstormed it on a digital board on FigmaJam.

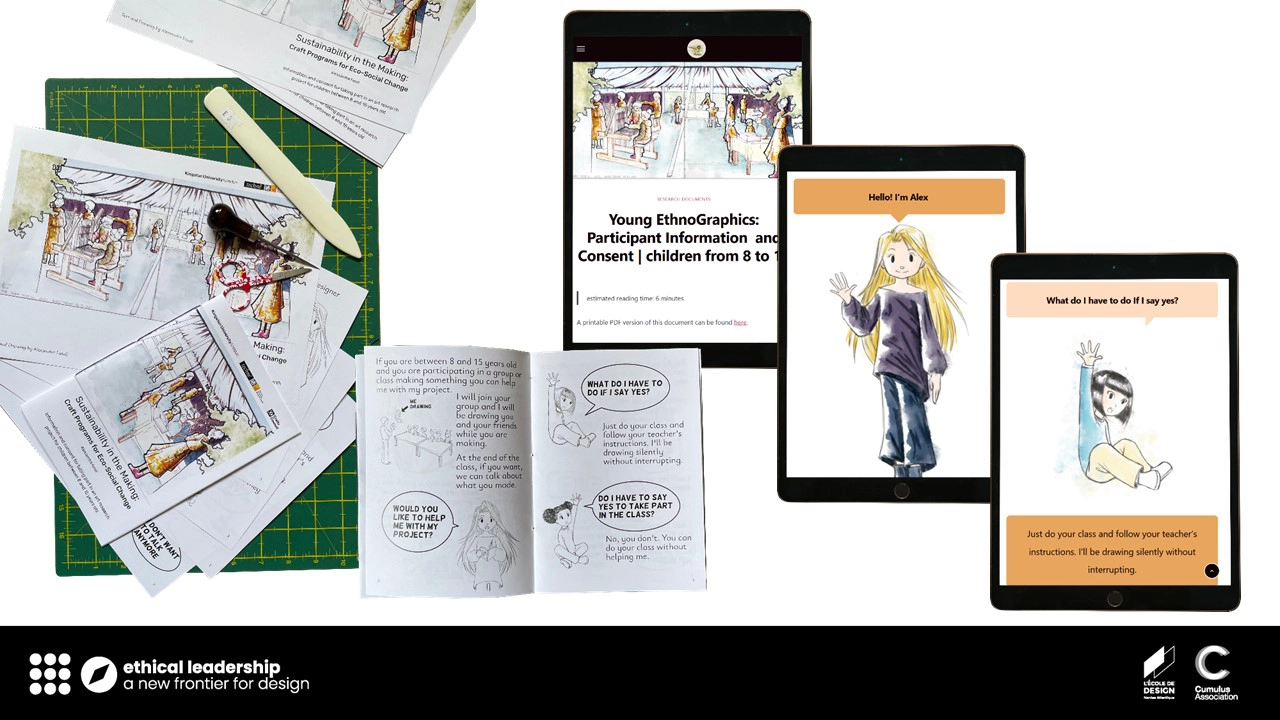

Using approaches from service design, I divided my participants into two main groups, adults and children, and from there I designed the participant information sheets in different formats that reflect the different media through which we consume and access information everyday. The structure of the documents fit all the protocol requirements, but they presented as a an interview and uses the typographic layout used in newspapers, so that it is visually recognisable. I included examples of ethnographic drawings that I did in some pilots, and that resonates with craftspeople, who in general value artistic practices. Finally, I crafted a whole website that not only contains the digital versions of the documents, but gives the whole research a more recognisable shape.

The participant information sheets for children are designed as a comic, the printed version being also a colouring book, while the digital version mirrors web comics layouts and is responsive and accessible from various devices. Language has been adjusted to the different age groups and the hand-sewn binding of the printed versions recall craft projects and scrapbooks.

The overall response by the people has been positive, as the creative aesthetic resonates with craftspeople, some even expressing enthusiastic feedback on the documents' aesthetics. In most cases, it succeeded in laying the ground for trustworthy relationships through a shared "craft language", which resulted in fruitful discussions during and sometime even out of the study.

However, there have been also people that refused to take part or that did not take the study seriously as this approach diverge from a mainstream idea of "serious research".

In short, approaches like mine still have drawbacks and cannot guarantee participation in a study.

While preparing all these documents has been a lot of fun, their production is very time consuming and I do not have data to say whether this approach has improved participation in my research.

So, is it worth? There is no clear cut answer.

We might start with the observation that, as Greaber reminds us, "paperwork is boring". It's boring for us, as researchers, and it's boring for our participants. Paperwork detaches the "act of getting informed" in the *informed consent* from the experiential process required to acquire information, that, by consequence, unmoors *ethics* from the moral and relational values that govern and guide our (inter)actions.

If the "power of design" relies in its capability of reshaping and creating services that are more accessible, more human (or even 'more than human') centred, then practical design skills are one of the best tools to rethink procedural ethics as part of a research experience, where *informed consent* is a relational process instead of a signature on a paper.

The value of research lies in its capacity of producing knowledge with, for, and by the collective. If we don't ground the design of ethical procedures in these principles, than what are we really valuing in design research?

References

Graeber, D. (2012). Dead zones of the imagination: On violence, bureaucracy, and interpretive labor: The Malinowski Memorial Lecture, 2006. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 2(2), 105–128. https://davidgraeber.org/papers/dead-zones-of-the-imagination-on-violence-bureaucracy-and-interpretive-labor/ . https://doi.org/10.14318/hau2.2.007

Social Research Association. (2021). SRA Research Ethics guidance 2021. https://the-sra.org.uk/common/Uploaded%20files/Resources/SRA%20Research%20Ethics%20guidance%202021.pdf