Making as Culture: people, places, practices, and sustainability change

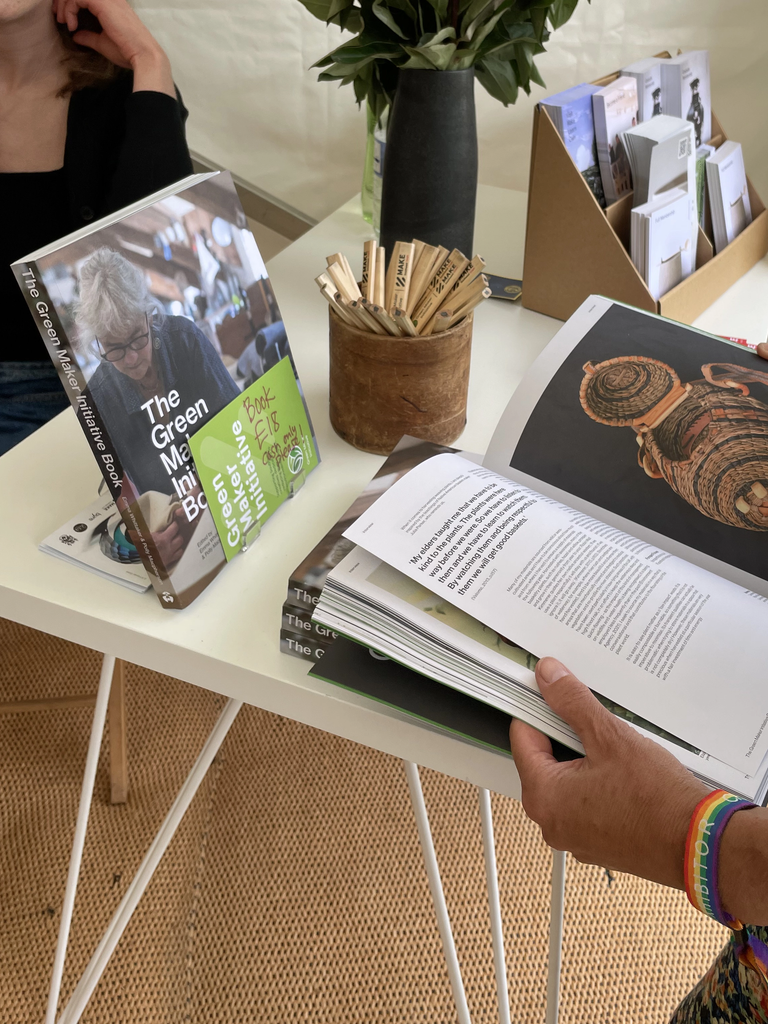

This book chapter "Making as Culture: people, places, practices, and sustainability change", published in the edited volume The Green Maker Initiative Book, is the first publication coming out from my PhD Sustainability in the Making: Craft Programmes for Eco-Social Change.

The Green Maker Initiative Book, edited by Emma Whittaker and Polly Macpherson, is part of the larger craft programme The Green Maker Initiative, started in 2021 through a collaboration between University of Plymouth's Low Carbon Devon and MAKE Southwest, the craft organisation that now leads the project.

The book contains a series of interviews and essays from makers, researchers, and craft experts reflecting on the the relationship between craft and sustainability.

My essay reflects on the definition of making as a cultural tool, the core principle of my research.

Here is the introduction paragraph:

Making Identities

When I was a child, I spent most of my holidays with my grandparents. Every day I was sitting with one of them, learning some practical skills: sewing my own pencil case, mending my clothes, repairing a variety of tools, and, in line with Italian traditions, making my own pasta, from the dough, to the shape, to the cooking. Their house was full of objects that they made themselves. Despite enjoying this time, I grew up wondering why they were spending so much time making stuff, when they could go to the shop and buy it. It was not until much later, that I understood that for my grandparents, who migrated to Rome from an isolated rural village in Sicily, making was a matter of identity, not of economy.

The perception of handmade skills has changed since my childhood time with my grandparents. As with every cultural practice, making evolves and is influenced by societal changes. In the 19th century, the rise of industrial manufacturing recast the modern perception of craft into high artisanal skilled work in opposition of the industrial unskilled labour (Adamson, 2013, p. 27). In Western popular culture of the 1950-1960s, Do-It-Yourself (DIY) practices evolved into a leisure domestic activity for (mostly white) middle-class families ; while in the 1970s the socio-economic climate in North America and Europe contributed to a ‘craft revival’, when a new ideological attitude towards the handmade gave craft a new political meaning (Peach, 2013, p. 168). This laid the foundation of another cultural shift in making practices that started in the beginning of the 2000s, when craft, DIY and hacker cultures met. With the exacerbation of the environmental crisis, many craft and DIY practices in the last two decades have evolved into social movements to resist a capitalist order (Marotta, 2021, p. 640), and are often associated with more sustainable, alternative ways of production. New maker identities have started to emerge, and in the West they can be identified in two main making approaches.

The first approach is rooted in the traditional idea of craft and artisanship as a particular skilled approach to making and knowledge (Thorlindsson, Halldorsson and Sigfusdottir, 2018, pp. 118–119; Zhan and Walker, 2019, p. 487) and the higher value attributed to handmade objects resides in their direct association with their creator (Väänänen et al., 2017, p. 259), who is celebrated and encouraged as an authentic, autonomous and creative worker (Munro and O’Kane, 2021, p. 6) who takes pride in the evolution of their skills (Sennett, 2009, p. 295). Building on the slow process of craftwork and its deep connection with local tradition and identities (Zhan and Walker, 2019, pp. 485–486), in environmental discourse handmade practices are conceptualised both as a way to reduce overconsumption, and as a healing process to escape the alienation of the industrialised society (Black and Burisch, 2020, p. 15). In this context, engaging with craft can be a way to manifest dissent (Mason, 2019, pp. 179–183) and a way to reconnect local traditions to a more sustainable lifestyle (Väänänen et al., 2017, pp. 259–260). Sustainable behaviours in craft have been associated with a combination of practical, social, personal, and economic considerations that construct an ensemble of values that inform those behaviours (Walker, 2018, pp. 46–48). These values are rooted in local cultures, sometimes described as a resource for developing ‘models of collective entrepreneurship’ through participatory design approaches that preserve local identities (Marchand et al., 2018, pp. 144–145).

A second approach, arising from the encounter of handmade and DIY traditions with the open-source hacker movement, is a techno-based and innovation-driven making practice that blends engineering, electronics, industrial design principles, and craft. Here, makers often engage with DIY practices from a ‘prosumer’ perspective, meaning they become producers and consumers at the same time (Ritzer, Dean and Jurgenson, 2012, p. 379). As this approach to making gained popularity in the beginning of the 2000s through the opening of makerspaces worldwide, it started to be referred to as the maker movement (Dougherty, 2012, p. 12; Hepp, 2018, p. 4). Makerspaces, sometimes called fablabs or hackerspaces, are generally defined as open community workshops where people can learn, share and make using digital and analogue tools (van Holm, 2014, p. 3; Niaros, Kostakis and Drechsler, 2017, p. 1144). They are the physical spaces where the maker movement manifests. Popularised through Maker Media’s MAKE: magazine and worldwide events like ‘Maker Faires’ (Hepp, 2020, pp. 943–944), in makerspaces making assume a new hybrid role between traditional craft and digital manufacturing, generating a brand new identity of the ‘maker’ (Hepp, 2018, p. 5; Rossi, 2018, p. 182; Marotta, 2021, p. 639): a ‘maker 2.0’, as Rossi (2018, p. 183) defines it, that expands the canonical idea of artisanship to a series of practices previously excluded in the definition of craft. The essence of this new maker identity is summarised in Dougherty’s (2012, p. 11) famous claim, “We all are makers”. However, Maker Media’s ‘maker’ image has been criticised for perpetuating a gendered, white, well-educated middle-class image of makers (Rossi, 2018, p. 191), while making in makerspaces is often approached through a Western-centric neoliberal entrepreneurial perspective (Sherlok, 2020, p. 127). In relation to sustainability, the growth of a makerspaces’ network and the promotion of open-source approaches gave rise to the concepts of ‘personal fabrication’ and ‘distributed manufacturing’ (Hamalainen, Mohajeri and Nyberg, 2018, p. 689), described as a sustainable alternatives to the current centralised industrial model (Cutcher-Gershenfeld, Gershenfeld and Gershenfeld, 2021, pp. 66–67). Researchers highlighted how culture and sustainability are ingrained in a wider makerspace narrative (Kohtala, 2017, pp. 387–388; Millard et al., 2018, p. 4), although the role makerspaces can have in changing consumption and production behaviours is unclear (Sherlok, 2020, pp. 126–127).

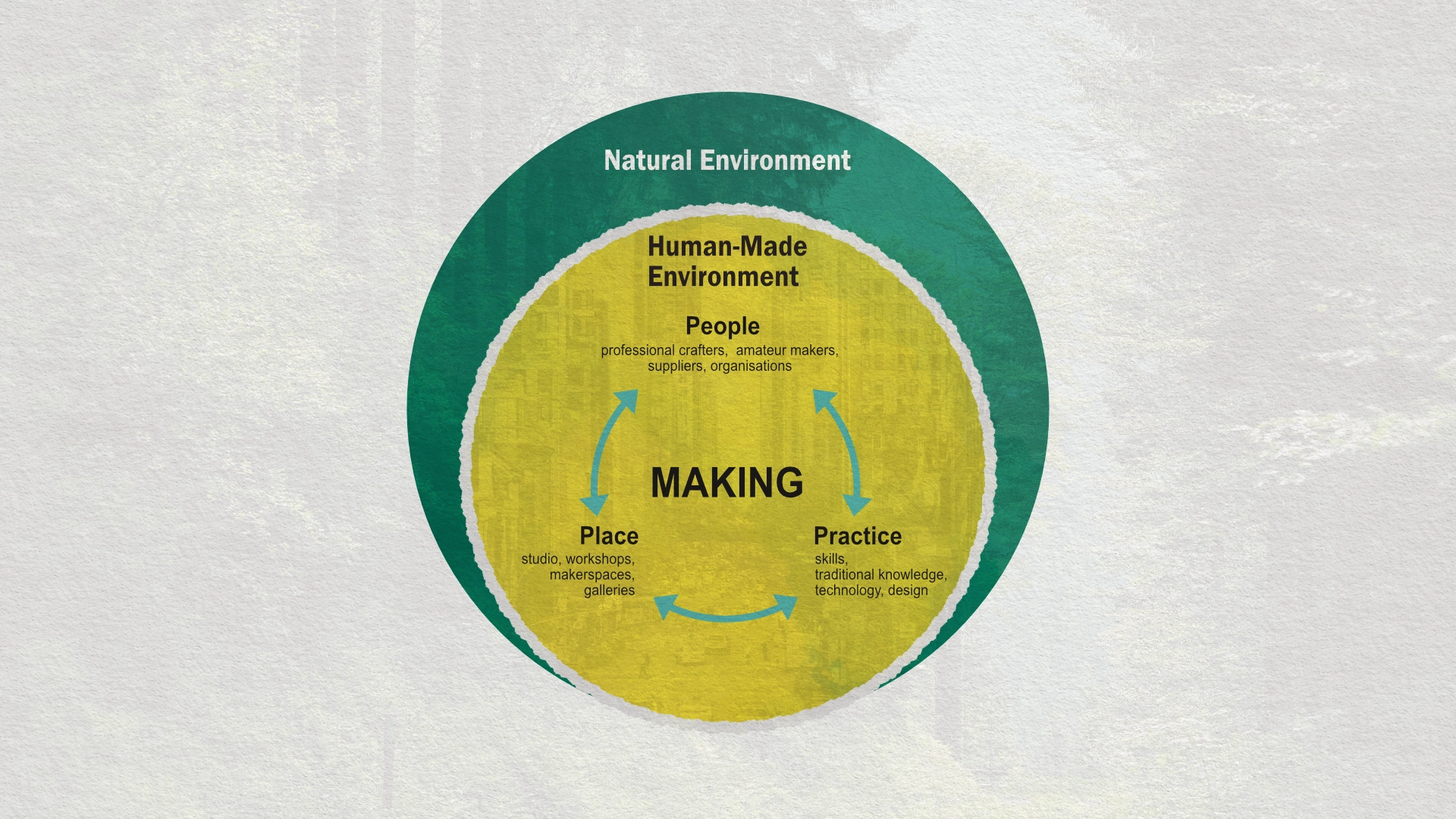

Traditional craft practices and the maker movement are not the sole ways making is framed in the West, however they are the most recognisable and widespread. Though they are sometimes intertwined, they build on two different ontological views of making, which influence how they define and address sustainability in and through their praxis. While both approaches are associated with more sustainable production models, most discourse focuses on product design and economic aspects, overlooking the cultural meaning making has in society and its implications for sustainability change. From a cultural perspective, making is both a cultural enabler and a product of culture. As a cultural enabler, making is a relational activity that can help foster cultures of sustainability by rendering environmental and ecological concepts tangible, helping communities to make sense of the current climate crises, and enhance climate action. However, making as a product of culture inherits existing biases and cosmologies present in the communities, reproducing structures and behaviours that might be in contrast with environmental and social goals. Though the cultural dimension in sustainability has been introduced later in environmental discourse, there is a growing attention on the importance of culture in sustainability change . Framing making as culture, I argue, can help in identifying values and biases in sustainability maker-led initiatives that can therefore be addressed accordingly to strengthen their potential in generating environmental actions through making.

The book, published by University of Plymouth Press and printed with vegetable inks on recycled paper, is available at MAKE Southwest, both at their gallery shop in Bovey Tracey and online: https://makesouthwest.org.uk/shop/p/the-green-maker-initiative-book